I chose to write about this photo, taken by Anne Rhett, because I think it very accurately illustrates my experience working at Elerai, a primary government school. Each day we would pull up to the school and…BAM!…kids flew from every classroom and corner of the playground to greet us with tremendous enthusiasm, broad smiles, and many, many “hellos.” For me this image really captures the intensity of the energy we faced at Elerai. Of course such excitement is wonderful, but it was also very draining. At the end of each day working at Elerai, I found myself utterly exhausted. I was also overwhelmed. The government schools are of course where the students are most deprived, so we want to focus our resources there, but figuring out the best way to do so is tricky. Leading LTP projects was very difficult because we did not speak Swahili and the students did not speak English. Furthermore, the classes were enormous (100+ kids in each classroom), and the class periods were short (just 40 minutes). The quantity of children, the short window of time, and the struggle to communicate made for a very challenging week. We quickly identified that right now in the government schools it might be best to focus more on producing great quantities of curriculum materials (posters, flashcards, pictures, etc.) and less on having the students take photographs themselves. This may seem to go against what LTP is all about but really so much of LTP is about closely studying photographs, noticing details, drawing conclusions from clues in the photographs, and writing; all of which be done without a camera.

Monthly Archives: August 2009

Elerai Primary School, examples

WHEN I WAS YOUNG I USED TO PLAY FOOTBALL WITH MY FRIENDS. THIS IS THE GROUND WHERE I USED TO PLAY FOOTBALL.

WHEN I WAS A BABY I USED TO CRY. WHEN WE WERE YOUNG WE USED TO CRY. WHEN WE WERE FIVE YEARS OLD WE USED TO BE UNHAPPY.

Connecting math to real life with LTP, a reflection by Rachel Blum

Math has often been classified as one of those subjects that students either have a gift for or will never fully understand. But what if this is more reflective of the teaching style associated with math rather than the subject itself? The photo above was taken at St. Joseph’s secondary school for girls with the Form 3B math class. The teacher had attended the LTP workshop and believed photos could be used for math but just did not know exactly how. He handed us the textbook, discussed the current topics and left the details of the project in our hands. We flipped through the pages to find distribution graphs followed by the definitions of mean, median, mode and range –topics that lend themselves to participatory learning by simply using the facts from the students’ lives for data. The idea of a human distribution graph as seen in the photograph arose as a solution to incorporate photography into a math lesson.

The next day the teacher first lectured to review the material. The girls raised their hands reciting perfect definitions and correct equations for each of the measurements. They seemed to have a great grasp of all of the concepts. The activity would be simple—a quick assembly into lines according to their number of siblings and then easy calculation using the familiar equations. However, when we met the class in the courtyard and finished explaining the instructions and outlining the project, we were met with blank stares and still bodies. We pointed to the imaginary x- and y-axis, but it seemed that when we left the paper and pencils in the classroom, we also left behind much of the familiarity of the material. Their comprehension of the subject was sufficient to answer questions on the board comprised of arbitrary numbers with the use of the different equations but did not allow them to arrange themselves according to their personal information. The process took much longer than expected and included many questions that required the students to make the connections between their work in the classroom and the human simulation.

The project proved to be a success on a variety of different levels. The human distribution graph introduced the students to a highly participatory learning experience that enhanced their comprehension of material from the actual curriculum. In theory, the involvement in this type of simulation followed by the calculation and analysis of data could ultimately improve some individuals’ test scores. Furthermore, the activity identified the limitations of the current style of teaching. One student claimed this project finally allowed her to see an application of math in the real world. Too often math is taught on the abstract level of arbitrary numbers with examples that have no connection to the real the world. Many students simply need a way to view the numbers in the context of their daily lives.

Take a step back, a reflection by Esther Jeohn

Take a Step Back

It is always interesting to see LTP working in people of all ages, whether it is in teachers or students. We have been working mostly with younger children in primary school, so I was a bit apprehensive as we went into St. Joseph’s Secondary School this week. We decided to work with Form 3, or the equivalent of 9th graders in the United States.

Not only was I apprehensive about the age group, but the subject matter was also a concern. We decided to work with Math and Biology, two subjects in which I had never worked with LTP before. However, we came up with a great idea for Math. The students were learning the basic principles of statistics like mean, median, and mode. Why not make a human frequency graph of the students?

So we decided to make a visual graph of the number of brothers and sisters that the students had. I was designated as the photographer and walked up four flights of stairs to try to fit all the students in. As I stood on the fourth floor and watched Kaitlin, Rachel, and Emily explain to the students about these concepts, I got to see a different perspective from what I usually see. I am usually involved in the teaching, but this time I got to observe what was happening.

The highlight was probably seeing the “click” go off in some students’ heads. I might have mentioned before that this is my favorite part of LTP. But I had never seen it from this angle where I would see students’ heads bobbing up and down as they nodded, showing that they understood the concepts.

St. Joseph’s showed me that first, LTP works at any age, and that second, sometimes you just need to take a step back and observe.

A reflection by Emily Hadden on St. Joseph’s LTP Math project

I believe this photograph to reflect our time spent at St. Joseph’s Secondary School quite accurately- the organization, the linear peacefulness, and the poised young women. In what was a much-needed change from the chaos of our work at several government primary schools, St. Joseph’s allowed us to appreciate the discipline and intelligence of each individual student. For Form IIIA Math’s project, we did a “human frequency graph”, in which each student represented a data point of the number of siblings they had in their family. This graph highlights the girls’ obedience and dedication to education, which was evident from our first entrance into their classroom, but was even more obvious when they neatly and quickly found their place on the “graph”. In addition to showing off the girls’ admirable traits, it also shows off how we learned from each other. That is to say, the graph showed us how families can come in all shapes and sizes. For St. Joseph’s girls, the average number of children is around three or four, and most notably, a girl in our class was one of twelve. For the majority of our DukeEngage group, our nuclear families are much smaller, and none of us come close to having eleven brothers and sisters. Thus, this project not only helped the girls learn statistics but it helped all of us learn about the cultural differences in family size and dynamics. It was a great way to wrap up our time spent working at schools in Arusha.

The need for visual classroom resources, a reflection by Nick

These photos, I think show how currently public schools in Arusha have very limited visual resources in their classrooms. These pictures were taken when a teacher brought in a visual aid he had stored away in the office. The only place in class for the 80 students to see was atop the blackboard, nailed into a cracking hole in the wall, hammered with a rock. This process alone took about 10 minutes—from finding the poster, to figuring out how to nail it up. The students then had to take turns in groups of three or four to come up and then balance on top of a rickety desk to catch a three-second glimpse of the visual. This method, although useful, I think can be dramatically improved through a simple application of LTP ideas. In this class, our project was to make individual photographic examples of the same visuals presented in similar posters or in their lecture books. Instead of having penciled or drawn sketches, the students could see actual living examples of the plant samples. This also allows the students to stay at their desks, and pass the images around without creating such chaos.

If public schools like Daraja mbili began to print out or photocopy simple visuals, such as maps and pictures, and have these available to pass around each desk, the classroom dynamic would be greatly improved. I think that at this moment, the idea to have each student go out and photograph is a bit idealistic, and mostly impractical. The school and students would reap greater benefits if they had reusable laminated visual aids. These could be produced by the LTP club for example, which Daraja Mbili has implemented. Also, when students are presented with a camera, especially at the secondary school ages, their attention shifts to a recreational one, and they would sneak out and take glamour shots when unsupervised. The visual concept of having themselves in the picture masks the creative and instructional aspect of their work. Taking this out of the equation, and presenting an already completed visual aid, although not as involved/participatory, still has a positive effect in the public education system.

N is for Neo-Colonialism, a photo reflection by Anne Rhett

They say a picture is worth a thousand words.

What they fail to mention is that in some cases, as that of the Polaroid above, one word can be more than enough. One too many, even.

It all started at the Themi Secondary school LTP teacher workshop. Our history-themed alphabet project was going swimmingly. It was all click-flash, business-as-usual until letter “N” was upon us…

Suddenly, a bit of commotion arose from the teachers’ circle, in Kiswahili of course. Then came the wild gesticulation in my direction. Okay. Then there was ambush- I was dragged into the frame, flanked by two giggling Themi teachers.

I remained calm.

For better or worse, it appeared I was essential to this photo-but why, oh why? I glanced quickly at their list.

N is for…Nationalism?

Alright, Tanzanian Nationalism…I can get on board with that! I thought, embracing them with an enthusiasm I typically reserve for the Christmas card and flashing a megawatt grin to match.

But nationalism our “N” was not, something I discovered with sinking stomach during the labeling phase of the project, as I watched that N be followed by many highly unanticipated letters.

Turns out I had unwittingly situated myself in the center of the image intended to represent NEO-COLONIALISM. There I was, in all my fair-skinned, beaming glory—the newly minted posterchild for legacies of oppression, exploitation, self-service and condescension –all the things from which we volunteers try so hard to disassociate ourselves.

To all outside eyes, this would indicate a huge DukeEngage Academy FAIL. Chloe would not be happy about this, I thought.

Later on, when the photographer explained her understanding of neocolonialism, it was clear that she meant to convey none of the irony, none of the insult that I had mentally extracted. All she meant to do was depict the new, friendlier type of relationships that occur between native Africans and those of European descent.

But despite her innocent intentions, the glaring label- or mislabel- remained.

And the real kicker was this: In many ways, I was not sure how far from accurate the caption truly was.

Many times over the course of this trip I have wondered how our “service” appears to those we are “serving.” We interrupt normal school schedules to introduce our concepts, methods we are sure they will benefit from.

We criticize their way of doing things- their system of education is too rote, too regimented, not free, creative or process-oriented enough. And, despite the pains we take to emphasize our commitment to partnership, collaboration and enhancement, the subtext is always there: our way is better. They can learn from us.

I can only hope that the legacy we leave here will inspire 999 other words.

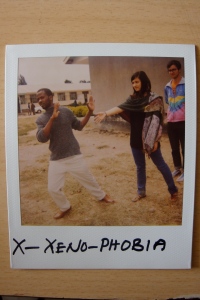

“X – Xenophobia,” a photo reflection by Marissa Bergmann

“X – Xenophobia”

Two Mondays ago was the first day of classes for the government schools, and suddenly there was a new wave of children on the streets. “Mzungu! Mzungu! Shikamoo, mzungu!” Mzungu is the Swahili word for “white person” or “foreigner.” I’m told it doesn’t carry much of a negative connotation, but it definitely stems from a visual difference: the way we look. I also get, “Mchina, mchina!! Hoi hoi hoi!”… Mchina meaning “person that comes from China” and the “hoi hoi hoi” an imitation of Asian language. I can’t say I’ve ever been discriminated much against racially, save the occasional Asian or “World War II” joke, so it’s a strange feeling to walk around every day and feel different because someone or another points it out. . . a group of children in forest green school sweaters and black & white striped socks, a man hanging out of a dala dala (cheap local transportation), a toddler barely able to walk clutching his mother’s hand . . . and even when it’s not said outright, you can feel it from the stares, the body language. . . it’s just a weird feeling. It wears you out. It’d get to the point where I just couldn’t respond to the children I passed at the government school, or else I’d snap. Any word that left my lips would be imitated in high voices. I felt mocked, and although that may not have been the intention, it upset me.

The photograph above is from a teacher workshop we held at Themi Secondary. The theme of the alphabet was History, and my group had S, T, U, V, W, and X.

S – Slaves

T – Trade

U – Union

V – Violence

W – Weapons

X – Xenophobia

(The History-themed alphabets teachers and students have made in Tanzania are pre-dominantly about War or Trade, every time.)

We got stuck on X and resorted to the dictionary, where one of the teachers found Xhote (a language spoken in South Africa) and Xenophobia. They chose the latter, simply because it’d be easy to photograph because hey-we’ve-got-a-mzungu-right-here! “You be in the picture, that’s easy!” (sigh) As in all LTP shootings, we try to give as little direction as possible to the actual construction of the image, so I was told what to do. Nick happened to be nearby, and just as they were about to shoot him out of the frame, they issued him back.

The image is comical, but also unsettling. I know that some people actually do feel this way about visitors. “Go back to your own country, we don’t want you here,” I was told on the street one day. To be fair, this was said after I refused to buy something, but the comment still stuck in my brain. Often I feel welcome, but there is almost always this tension, a mistrust or wariness. Of course I don’t go around stretching out my hand toward people aggressively but I look at it and see it as symbolic of one view of this type of international social service. I guess the key is to recognize when somebody doesn’t need or want you to be there. In most cases, I would say I’ve felt welcomed and appreciated, so long as I am open and flexible to things such as a constantly changing schedule (or complete disregard for “schedule”), cultural differences, and misunderstandings. When the approach is positive as such, it is no longer “service,” but more of an interaction between people learning from each other.