My entire life, people have wanted to know about my faith. They ask a lot of questions. “What religion are you?” “Do you believe in God?” In Africa, at one of the teacher workshops, I got: “Are you Christian or Muslim?”

These are questions I’m not particularly good at answering. I’ve found something that works alright: “I am open-minded and I like to learn as much as I can.” It doesn’t really cover it all. But it is true.

Though my religious identity isn’t clear-cut (whose is, really? Faith is difficult), my life has not been without religion. I went to Jewish daycare and preschool and still eat matzo all the time as a snack. I went to many Christian churches and a few camps with my friends growing up. I went to Unitarian Universalist church for a while when I was little – I loved to light candles at the services, and I read the magazine whenever it came in our mail. I also read the books on world religions that my mom bought us, and in middle school and high school, I enjoyed looking up and finding meaning in spiritual and philosophical quotes online. In college I seemed to befriend the entire Jewish population of the greater New York area and celebrated my first Passover this year. I just spent two months in a very Muslim community in Africa during the holy month of Ramadan. I don’t belong in any one place. I have learned about many places, and felt benefits of many of them, but I have felt that I don’t completely fit anywhere.

Not that it’s anyone’s business what I do or don’t believe, but I’d rather put something out there than have people fill in the gaps with their own assumptions. Another thing I’ve had going on my whole life is having people try to speak for me or give me what they think I need. No one has bad intentions, but I’ve realized that I need to speak for myself. My parents advised me that I shouldn’t talk about religion or politics with people because those conversation subjects can lead to conflict quickly if there is disagreement. I don’t like conflict. I have a very diplomatic personality. My fourth grade teacher called me “peacekeeper”. Sometimes it makes sense to hold my tongue to keep things running smoothly. But it’s also not fair to stay silent to keep someone else comfortable if it hurts me.

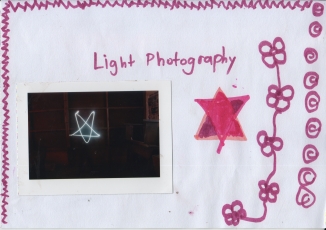

In the loosest possible (and probably most cliché) wording, I believe in something bigger. Love, movement, light – powerful things we can’t touch, but we can feel. In the slower moments of the last two months, these strong forces have been working together, around me. I often found myself in awe, taking it in, reflecting on their presence, my presence, and the presence of everything else.

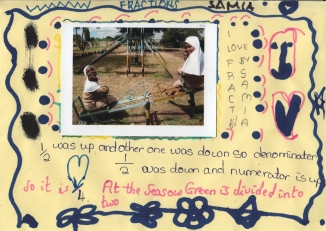

One week, I was working with a group of students to come up with words for a photographic alphabet about dreams. For G, one suggested God. Oh boy. I wasn’t sure how we were going to visualize God in a picture, and I worried that it would probably be offensive.

We headed outside and I asked the kids for ideas of what to photograph. Simultaneously, they all pointed up to the sky. I couldn’t help but laugh. Okay, yeah, we’ll put the sky in the picture. It made sense. The sky doesn’t begin or end, it surrounds. Sounds like the right idea.

But we need to make this picture about God. Not the sky. How will we do that? Why is God important? What does God mean to you? Why did you choose God for dreams?

Selemani, a fifteen-year-old boy, told me that he prays to God to help him through his life and to accomplish his goals. To represent that, he asked another student to take the picture below:

He is praying. Behind him is the sky, supporting him, letting him shine, yet beautiful on its own. This picture took my breath away because of its universality. I think it shows what people get out of religion and spirituality – he looks so peaceful. It shows things that cannot be seen. I saw a quote at Shalom School that says it better that I can: “The beautiful Hebrew word ‘shalom’ means ‘I understand, being complete, having all a person requires for a happy and meaningful life. It encompasses the whole of human life: spiritual, intellectual, social and material. The world desperately needs shalom.”

Religion is such a huge part of Tanzanian culture, so I found myself reflecting on it even more everywhere I went.

I went shopping for kangas, beautiful pieces of fabric with African designs and Swahili sayings. I was trying to find one with a saying that was meaningful and relevant to my life. Many of them were religious in nature, and since I was thinking that religion wasn’t a huge part of who I was, I was trying to find one that wasn’t. I ended up finding a gorgeous navy blue piece with gold stars that I couldn’t pass up. The saying on it was “Ee Mungu Twakushukuru”, which translated to “Oh God, we thank you”. At the time, I thought that even though that phrase wasn’t ideal for me, I had to buy it anyway.

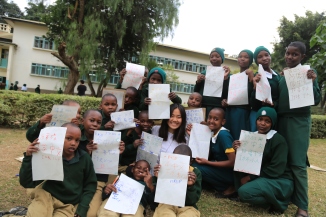

I got the kanga made into a dress that I wore on the last day with the students in my afterschool dance program. They were very excited that I was wearing it, exclaiming, “Teacher, this is our culture!” and “Teacher, you look smart”. They held the hemline of my dress gently and slowly read it aloud. “Oh God, we thank you, teacher, it is nice.” And I felt thankful, looking at their deep brown eyes, their polite smiles, for whatever force, however godly, brought us together, if only for a little. As we hugged goodbye, my oldest one whispered, “God willing, we will meet again.” I breathed in the sweet scent of their little heads. They always smelled like soap. (Meanwhile, as a camp counselor I’ve noticed that American kids, though also lovable, smell like spit.)

Our group was spirited. I watched them dance and smile and I watched the sunlight catch the dust that they kicked up. Somehow, we were all there. We weren’t alone, either.

I’m home now. We talked a lot about our homes, our privilege, in reflection sessions. It was something that was always on my mind – why was I born where I was, with the family, things, and opportunities I have? What energy in the universe laid out my life that way?

It is a privilege to reflect on privilege. To feel lucky for all the good things that I have. To think about all of the blessings that I have been given, whoever or whatever gave them. I think that they were given, because I have received them. I have felt, seen, taken in many small wonders. I’m still not really sure I can put it into words. I am not sure that is something that I will ever be able to do. Perhaps some things in this world are just too big for that.

Colors. Some can see red, pink, orange, yellow, green, blue and purple. But, I … I see light yellow, I see lime green, seafoam green, cerulean, carmine… I see golden yellow, and sunset orange, and ultramarine blue.

Colors. Some can see red, pink, orange, yellow, green, blue and purple. But, I … I see light yellow, I see lime green, seafoam green, cerulean, carmine… I see golden yellow, and sunset orange, and ultramarine blue.